Lexington is a small city in the heart of the bluegrass. When I say small, I mean small by the megapolitan standards of the present titanic world: a bare quarter million souls or so. Compare classical Athens or Florence, forty or sixty thousand strong, that created arts, sciences, and culture to endure centuries. Our present era makes us larger in numbers, in mass, in reverberations of one active voice against the past, and smaller, more self-similar to our hordes of contemporaries than the past.

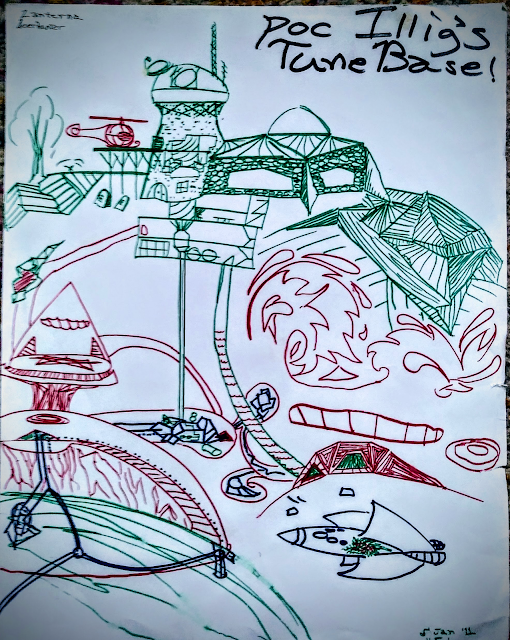

My world was the library, my imagination, my drawings and creations, and my church. These spheres gave me expansion and constriction. To the library fell the exemplars of knowledge across some dozen spheres. (More, of course, were available, but I did not avail myself of much more beyond kids' books, atlases, sharks & lesser domains of archaeology, gemstones & lesser crystals, geography, geology, weapons, sea-ships, rocket ships, astronomy, classical monsters, and mythology.) From my imagination rose narrations of heroic deeds and titanic machines, mostly expressed in drawings and stories told to myself while falling asleep, stories heavily based on Star Wars, Battlestar Galactica, the Bible, ninja lore, and whatever inchoate regions of the subconscious rose within my sleeping brain. My drawings fed back upon my imagination and the seeds of inspiration, manifested in pencil on paper: spaceships, warriors, monsters, aliens, heroes—archetypal forms of the energies of humanity, for which the adult world has so little use. Finally, the church—a tiny Pentecostal assembly, with some thirty adults raising hands and throwing back heads in ecstatic release, with much glossolalia and apocalyptic "translation"—much separating of the sheep from the goats, many moons turned to blood and suns gone black in the year of our Lord 1986 or so—this was a high-intensity zone quite separate from the world of adventure children's cartoons and elementary school exercises. The church was a place of joy—who does not love singing and dancing and going around getting hugs from adults and the six kids you know, year in and year out?—and a place of isolation, for the expectation lay heavy on us: we were a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, and the world would try to destroy us.

As a boy of 8, 9 years, that holy priesthood weighed heavily upon me, and I found it hard to separate myself from the other boys and girls who loved rockets and dinosaurs and ninjas. Who were the sheep and who were the goats? What was the preacher's authority for what he boomed out at us? Why were the churchly grown-ups so obsessed with Israel and Evolution, the subjects they chattered about so endlessly? Every month the church folk went to a steak restaurant and ate steaks, and once a month we had a potluck where every family brought an entree or a dessert, and everyone ate to repletion in good fellowship, the apocalypse forgotten.

My home town had a major university, and historical sites, and horse farms, and factories, and a vast subterranean hollow filled with Cold War strategic materials: the limestone rock provided a solid structure for enormous excavations. But my family moved out of state in my 14th year, and I had never much gone beyond neighborhood explorations, the library, and the church.

My world was the library, my imagination, my drawings and creations, and my church. These spheres gave me expansion and constriction. To the library fell the exemplars of knowledge across some dozen spheres. (More, of course, were available, but I did not avail myself of much more beyond kids' books, atlases, sharks & lesser domains of archaeology, gemstones & lesser crystals, geography, geology, weapons, sea-ships, rocket ships, astronomy, classical monsters, and mythology.) From my imagination rose narrations of heroic deeds and titanic machines, mostly expressed in drawings and stories told to myself while falling asleep, stories heavily based on Star Wars, Battlestar Galactica, the Bible, ninja lore, and whatever inchoate regions of the subconscious rose within my sleeping brain. My drawings fed back upon my imagination and the seeds of inspiration, manifested in pencil on paper: spaceships, warriors, monsters, aliens, heroes—archetypal forms of the energies of humanity, for which the adult world has so little use. Finally, the church—a tiny Pentecostal assembly, with some thirty adults raising hands and throwing back heads in ecstatic release, with much glossolalia and apocalyptic "translation"—much separating of the sheep from the goats, many moons turned to blood and suns gone black in the year of our Lord 1986 or so—this was a high-intensity zone quite separate from the world of adventure children's cartoons and elementary school exercises. The church was a place of joy—who does not love singing and dancing and going around getting hugs from adults and the six kids you know, year in and year out?—and a place of isolation, for the expectation lay heavy on us: we were a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, and the world would try to destroy us.

As a boy of 8, 9 years, that holy priesthood weighed heavily upon me, and I found it hard to separate myself from the other boys and girls who loved rockets and dinosaurs and ninjas. Who were the sheep and who were the goats? What was the preacher's authority for what he boomed out at us? Why were the churchly grown-ups so obsessed with Israel and Evolution, the subjects they chattered about so endlessly? Every month the church folk went to a steak restaurant and ate steaks, and once a month we had a potluck where every family brought an entree or a dessert, and everyone ate to repletion in good fellowship, the apocalypse forgotten.

My home town had a major university, and historical sites, and horse farms, and factories, and a vast subterranean hollow filled with Cold War strategic materials: the limestone rock provided a solid structure for enormous excavations. But my family moved out of state in my 14th year, and I had never much gone beyond neighborhood explorations, the library, and the church.

Comments

Post a Comment